NO FRIENDSHIP WITHOUT TRUST

If God wants us to be his friends, why does he often seem so unfriendly

If God wants us to be his friends, why does he often seem so unfriendly

in the Scriptures? Doesn’t the Bible teach that if a man wants to have

friends, he should himself be friendly?

It certainly seems to say that in Proverbs 18:24, especially as it has

been translated in the 1611 King James Version:

“A man that hath friends must shew himself friendly:

and there is a friend that sticketh closer than a brother.”

Most people have probably discovered from their own experience the truth

of the first line of this proverb. You can hardly expect to have friends if you

are not friendly yourself. But to this day, Bible translators are not agreed

that this was the meaning intended by the Hebrew writer. Many variations of the

first line are offered in the versions.

Closer than a Brother

But translators seem to be agreed on the meaning of the second line: a

true friend sticks closer than a brother. The implication seems to be that the

friends in the first line cannot be trusted, and many versions translate

accordingly:

There are friends who pretend to be friends, but there is a friend who sticks closer than a brother. (RSV, 1952)

Some friends play at friendship but a true friend sticks closer than one’s nearest kin. (NRSV, 1989)

Some friendships do not last, but some friends are more loyal than brothers. (GNB, 1976)

When Jesus made the offer of friendship to his disciples, was he only

“playing” at friendship? Was he only “pretending” to be so

friendly? There can be no lasting friendship without mutual trust and

trustworthiness. Is there good reason to trust the Son of God as “a friend

who sticks closer than a brother”?

How are we to understand those “terrifying stories” that

seemed so forbidding to the Scottish gravedigger, those “more ferocious

aspects of the Scriptures” that the saintly Bible teacher hesitated to

discuss with her young pupils? Are those passages, perhaps, to be understood as

representing the character of the fearsome Father rather than his gentle Son?

Could the Father Be Like Jesus?

Philip was one of the disciples privileged to hear the Master’s invitation to understanding friendship. Evidently he too had been puzzled by the apparent difference between the friendliness of Jesus and what he assumed to be the picture of the Father in the Old Testament. “Jesus,” he requested, “show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied.”1

“Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still

don’t know me?”

“But our questions are not about you,” Philip persisted.

“We know and love you, Lord. And even though we worship you as God’s

Son, we are not afraid to be so close to you here in the upper room. The one we

have questions about is the Father. We want to know about the God who thundered

on Sinai, who drowned the whole world in a flood,2 who destroyed the

cities of Sodom and Gomorrah;3 the one who consumed Nadab and

Abihu4 and opened the earth to swallow up rebellious Korah, Dathan

and Abiram,5 who ordered the stoning of Achan and his

family6 and rained fire down from heaven on Mount

Carmel.”7

“Jesus, could the Father be like you?”

And the Lord replied, “If you really knew me, you would know the

Father as well. Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show

us the Father’? Don’t you believe that I am in union with the Father,

and the Father is in union with me? If you trust me, you can trust the one who

sent me.”

“And as for those distressing stories of discipline and

death,” Jesus might have continued, “do not misunderstand them to

mean that the Father is less friendly and approachable than you have found me

to be. Actually it was I who led Israel through the wilderness. The command to

stone Achan was mine!”

Paul understood this when he wrote, using the familiar Biblical symbol

of the rock, “They all drank from the supernatural rock that accompanied

their travels—and that rock was Christ.”8

If only Philip had gone on questioning, the disciples might have heard

some priceless explanations to record in the gospels. He could have asked,

“Why, Jesus, did you order the stoning of Achan and his whole family but

work to prevent the stoning of the woman caught in adultery? Why did you

thunder so loudly on Sinai but speak so softly to us now?”

Unfortunately the disciples were more interested in who got the best

places at the table and what positions they would hold in the future kingdom.

So now it is our turn to ask questions, and Jesus invites us as his

friends to pursue such understanding.

Why Did God Raise His Voice on Sinai?

Imagine being present on that awesome day when God came down on Sinai to

speak to the children of Israel. The whole mountain shook at the presence of

the Lord. There was thunder and lightning, fire and smoke, and the sound of a

very loud trumpet.

And God said to Moses, “Keep the people back. If anyone even

touches the mountain, he must be put to death. Whether animal or human being,

he must be stoned or shot. Set a boundary around the mountain. If anyone breaks

through to look at me, he will perish.”9

The people were terrified. “They trembled with fear and stood a

long way off. They said to Moses, ‘If you speak to us, we will listen; but we

are afraid that if God speaks to us, we will die.’”10

But Moses reassured the people that there was no need to be afraid, for

Moses knew God and was his friend. Though he always approached him with deepest

reverence and awe, he was not afraid. And the Lord would speak to Moses

“face to face, as one speaks to a friend.”11

Remember how fearlessly but reverently Moses responded to God’s

offer to abandon Israel and make a great nation of him instead.12

But all the way from Egypt to Sinai the people had behaved most

irreverently, grumbling and complaining—in spite of the miraculous

deliverance at the Red Sea and God’s generous provision of water and food.

How could God gain the attention of such people and hold it long enough to

reveal more of the truth about himself?

Should he speak softly to the people, in a “still, small

voice,” as he would speak years later to Elijah at the mouth of the

cave?13 Should he sit and weep over Israel as he would centuries

later, sitting on another mountain and crying over his people in

Jerusalem?14

Only a dramatic display of his majesty and power could command the

respect of that restless multitude in the wilderness. What a risk God would

thereby run of being misunderstood as a fearsome deity, hardly one to be loved

as a friend.

However, it was either run this risk or lose contact with his people.

Without reverence for God, they would not listen or take his instruction

seriously. This is why another Old Testament proverb teaches that “to be

wise you must first have reverence for the Lord.”15 And God is

willing to run the risk of being temporarily feared, even hated, rather than

lose touch with his children.

Would You Care Enough to Do the Same?

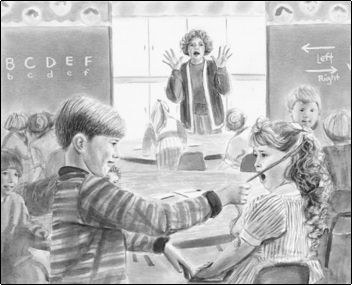

Parents and teachers should be well able to understand this risk.

Imagine yourself a grade-school teacher known for dignity and poise. In all

your years of teaching you have never found it necessary to raise your voice to

your young pupils. But now the principal has just urgently informed you at the

door that the building is on fire and you must direct the children to leave the

room as quickly as they can.

You turn and quietly announce that the building is on fire. But the room

is very noisy following the excitement of recess. No one notices you standing

there in front. Out of love for your roomful of children, would you be willing

to shout? Still failing to gain their attention, would you care enough to climb

on the desk, even throw an eraser or two? The children might finally notice

this extraordinary sight—their gentle teacher apparently angry for the

first time, shouting and gesturing as they have never seen her before! They

would slip stunned into their seats, perhaps frightened at what they saw.

“Now, children, please don’t go home and tell your parents

that I was angry with you,” you might begin to explain. “I was simply

trying to get your attention. You see, children, the building is on fire, and I

don’t want any of you to be hurt. So let’s line up quickly and march

out through that door.”

The Risk of Discipline

Which shows greater love? To refuse to raise one’s voice lest the

Which shows greater love? To refuse to raise one’s voice lest the

children be made afraid? Or to run the risk of being feared and thought

undignified in order to save the children in your care?

God runs this same risk every time he disciplines His people. “For

the Lord disciplines those whom he loves.”16

“Disciplines” is a better translation than the King James

Version “chasteneth,” which suggests only the idea of punishment.

The original Greek word is not limited to this. It means to

“educate,” “train,” “correct,”

“discipline”—all of which may call for occasional punishment, to

be sure, but always for the purpose of instruction.

This explanation of the loving purpose of God’s discipline is

included in yet another of Solomon’s proverbs:

My child, do not despise the Lord’s discipline

or be weary of his reproof,

for the Lord reproves the one he loves,

as a father the son in whom he delights.17

The book of Hebrews cites this proverb and then urges God’s

children not to overlook the encouraging meaning. “God is treating you as

sons. Can anyone be a son and not be disciplined by his father? If you escape

the discipline in which all sons share, you must be illegitimate and not true

sons. Again, we paid due respect to our human fathers who disciplined us;

should we not submit even more readily to our spiritual Father, and so attain

life? They disciplined us for a short time as they thought best; but he does so

for our true welfare, so that we may share his holiness. Discipline, to be

sure, is never pleasant; at the time it seems painful, but afterwards those who

have been trained by it reap the harvest of a peaceful and upright

life.”18

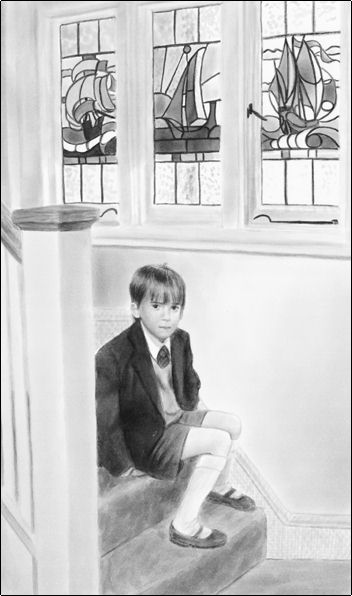

A Lesson Learned on the Bottom Stair

I realize now how much my gentle mother ran this risk of being

I realize now how much my gentle mother ran this risk of being

misunderstood every time she determined there was need for some especially

impressive instruction. The usual place for the administration of this

discipline was in the front entrance hall of our two-story home in England. On

one wall stood a tall piece of furniture with a mirror, places for hats and

umbrellas, and a drawer in the middle for gloves. In the drawer were two

leather straps. I never discovered why there were two, but in imagination I can

still hear the rattling of the handle on that drawer and the ominous shuffling

of the straps as Mother made her selection. Then we would proceed together

toward the stairs.

After Mother was seated and the culprit had assumed the appropriate

posture, it was her custom to discuss the nature and seriousness of the

misdemeanor committed, all to the rhythmical swinging of the strap. The more

serious the crime, the longer it took Mother to discuss it! I cannot recall

ever having thought while in that painful position, “How kind and loving

of my mother to discipline me like this! How gracious she is to run the risk of

being misunderstood or perhaps of causing me to hate her and obey her out of

fear!” On the contrary, I seem to recall very different feelings at the

time.

But when it was all over, I had to sit on the bottom stair and reflect

on the experience for a while. And before I could run out and play again, I

always had to find Mother and there would be hugging and kissing and

reassurance that things would be better from now on.

Sometimes repentance was a little slow in coming. I can remember

climbing to a higher stair so that I could look out through the stained-glass

windows at the flowers around the lawn. But it was hard to stay angry for long

or to go on feeling afraid. Mother never seemed to lose her temper. We knew

there was nothing she’d be unwilling to do for us children, and no limit

to her patience in listening to all we had to tell. She seemed so proud of our

successes and so understanding when we failed.

Recently I visited that bottom stair again. The stained-glass windows

were still there, but the stair seemed a bit lower when I sat on it this time.

Somehow I couldn’t remember the pain and embarrassment of it all. But as I

thought about my mother, who’s been gone for many years, I did feel a

specially warm sensation—but not where I used to feel it during the

swinging of that strap!

I hope I shall never lose the meaning of those sessions with Mother at

the bottom stair. She helped us learn an essential truth about God. Not that we

understood it right away. Mother was willing to wait. And if we had grown up

fearing and hating her for those times of discipline and punishment, it would

have broken her heart. But she cared enough about us to be willing to run that

risk.

God Much Prefers the Still, Small Voice

The message of Scripture is that God cares enough about his people to

run this same risk. It is true that if we insist on having our own way, God

will eventually let us go. He does not give us up easily, however. He

persuades; he warns; he disciplines. He would much rather speak to us quietly

as he finally could with Elijah. But if we cannot hear the still, small voice,

he will speak through earthquake, wind, and fire.19

Sometimes, at very critical moments, it has been necessary for God to

use extreme measures to gain our attention and respect. On such occasions our

reluctant reverence has been largely the result of fear. But God has thereby

gained another opportunity to speak, to warn us again before we are hopelessly

out of reach, to win some of us back to trust—and to find that there

really is no need to be afraid.

Surely in all this God has shown himself to be a friend who “sticks

closer than one’s nearest kin.”20 The one who wants us to

be his friends is so good a friend himself that he is willing to stick with us

when we are not very friendly toward him. Patiently he works to change even his

enemies into understanding friends.

How God Won Saul

God “stuck” with his enemy Saul and turned him into Paul, the

great apostle of trust and love. Before Saul met Jesus on the Damascus road, he

was utterly dedicated to eradicating what he believed to be dangerously false

teachings about God. If anyone had dared suggest that he was actually

God’s enemy, Saul would have been highly incensed. He had reason to regard

himself as God’s most zealous, hardworking servant and defender of the

truth.

But Saul worshipped an unfriendly god who would use force to have his

way. So in the name of the god he knew, Saul tried to force the early

Christians to give up their heresy and come back to the truth. If they refused,

he would have them arrested and even destroyed—just as he believed his god

would do.

That’s why Saul could assist in stoning so good a man as Stephen.

He did not enjoy the execution, but he “approved of their killing

him.”21 He remembered the story of Sinai. Did not the just and

holy God direct that the disobedient should be stoned or shot?

“Please Forgive Saul”

How could God win a man like Saul to be his friend, the friend of a

friendly God?

The Lord chose to confront his future friend on the road to Damascus.

Saul was troubled by his memories of that execution. Stephen had shown

remarkable knowledge of the Scriptures, and Saul’s conscience still

acknowledged the authority of truth.

Perhaps especially disturbing was Stephen’s prayer of forgiveness

just before he died: “Lord, do not hold this sin against

them.”22 There were reports that the heretic Jesus had behaved

the same way on the cross: “Father, forgive them; they do not know what

they are doing.”23 If these two men really were ungodly

heretics, how could they endure such torture with such godlike grace?

But, Saul could have reasoned, what about all those stories of divine

wrath and retribution, the exercise of justice in stamping out sinners and sin?

Had not the chief administrators and theologians authorized him to carry out

this unpleasant but holy mission? So Saul continued on his way to Damascus,

“still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the

Lord.”24

Would it have done any good for God to tap him gently on the shoulder

and inquire, “One moment, Saul, could I have a word with you?” Saul

wouldn’t even have felt God’s touch. He certainly couldn’t have

heard the still, small voice. First something dramatic must be done to capture

Saul’s attention.

In a blaze of light, God floored him right there on the road. More than

that, to ensure his undivided attention to what God had to say, he took away

his eyesight for a while.

As Saul lay helpless on the road, he must have been shocked to discover

that his assailant was none other than the meek and gentle Heretic he had once

despised as weak—teaching such nonsense as loving our enemies and even

praying for the Romans!

“But he could have killed me just now,” Saul may have thought

to himself. “I would have, if I’d been in his place. Why is he not

destroying me the way I’ve been destroying his disciples? Instead, I hear

him talking to me softly in my own language.25 And he’s talking

about my conscience!

“I’m sorry, Lord. I was terribly wrong. Now please accept me

as your servant, and tell what you want me to do.” Years later, in his

letter to the believers in Rome, Saul—now called Paul—was honored to

introduce himself as “a servant, or slave, of Jesus

Christ.”26

Paul, the Servant

But God wanted more from Saul than just submissive service. So he gave

him no specific orders at that time, except to get up and go on to Damascus.

“There you will be told all that you are appointed to

do.”27

A man named Ananias met him in the city with the friendly welcome,

“Saul, my brother, receive your sight again!”28 Then

Ananias went on to give a description of God’s great expectations of his

new disciple. Saul was to be God’s assistant29 in making known

the truth. “The God of our fathers,” Ananias continued,

“appointed you to know his will and to see the Righteous One and to hear

him speak, because you are to be his witness to tell the world what you have

seen and heard.”30

Paul, the Understanding Friend

As Paul reflected on God’s persuasive skill in treating him so

firmly but graciously on the Damascus road, he was changed into more than a

faithful servant. He became a most understanding friend, whose highest aim was

to witness to the truth about his Lord by treating others as God had treated

him.

“Imitate me, as I imitate Christ,” he wrote to the

Corinthians.31 Never again would he resort to the abuse of force. To

those who disagreed with him—even about important matters—he would

say, “Let everyone be fully convinced in his own mind.”32

And of those who felt free to criticize and condemn, he would ask, “Who

are you to pass judgment on another?”33

Paul showed how well he knew God, and understood the ways of friendship

and trust, by his Christ-like dealing with grossly misbehaving members of the

church in Corinth. At first he appealed to them with reason and love. It was to

them that he wrote the famous chapter on love that we now know as 1 Corinthians

13. But they were not impressed, and disdainfully rejected his advice.

Before Damascus, Paul would have known exactly what to do—imprison

them, have a few of them stoned! But now, of course, this was out of the

question. He decided to visit them in person, travelling from Ephesus to

Corinth. There he was rudely insulted as weak and vacillating. They scorned his

claim to be an apostle and challenged his authority to correct them at all.

Some scoffed, “His letters are weighty and strong, but his bodily

presence is weak, and his speech contemptible.”34 Obviously

they would not take him seriously until he did something to win their respect.

Paul returned to Ephesus to decide his next move. It seemed clear that

more gentle talk about love would only worsen the problem. Like the teacher in

the burning school, should he risk misunderstanding by sternly raising his

voice? Would they then accuse him of more vacillation, of contradicting his own

chapter on love?

He was committed to following the example of Christ—if only he

could know what the Lord would do in such a situation. But he did know.

Christ raised his voice on Sinai to win respect and attention. He raised it

again on the Damascus road, for which his former foe will be eternally

grateful.

Paul made his decision. He sent a blistering letter. It was so stern

that he cried as he wrote it. Worried that he might be misunderstood, he

couldn’t wait for a reply, and started out again for Corinth. He began to

regret what he had written, but only for a while. For on the way he received

the news that the emergency measure had succeeded. Raising his voice had

worked! The letter had been received with “fear and trembling.” And

with new-found respect, the apostle’s advice had been fully

accepted.35

Can the God Who Stoned Achan Be Trusted?

As Paul cried while writing to the sinners in Corinth, so God, too, must

have wept as he ordered the execution of Achan and his whole family. And he

required their fellow Israelites to stone them, then burn the remains. Could

such a God ever be trusted as a friend?

As they crossed the border into hostile Canaan, the people’s only

hope of survival lay in taking God seriously enough to follow his instructions

in every detail. There was danger that Achan’s rebellious and

disrespectful spirit would spread throughout the camp.36

In a day when life was held all too cheaply—the people had already

told Joshua that anyone who disobeyed him should be put to death—it was

necessary that God’s discipline be sufficiently awful and dramatic to make an

adequate impression.37 But as the stones were finding their target,

how the one who even sees the little sparrow fall38 must have hated

every horrible moment!

A Consistent Picture of God

A hundred and thirty-five trips through all sixty-six books, in company

with thousands of people, have served to convince me that the Biblical record

reveals a consistent picture of an infinitely powerful but equally gracious and

trustworthy God, whose ultimate purpose for his children is the freedom of

understanding friendship.

As he works toward this goal, he is willing to stoop and meet us where

we are, leading us no faster than we’re able to follow, speaking a

language we can respect and understand. To keep open the channels of

communication, he has often resorted to measures that risk misunderstanding.

To his enemies and careless observers, these are acts of an unfriendly

God. But to understanding friends, they are further evidence of God’s

trustworthiness that is the basis of their trust.

And without such trust, there can be no true friendship.

14. See Luke 19:41–44; 13:34; Matthew 23:37.

29. A word used for assistants to physicians, kings, the Sanhedrin, or in a synagogue. Some versions offer the translation “minister,” as also in Luke 1:2, “ministers of the word.”

34. 2 Corinthians 10:10, NRSV.

35. The whole story is told in 2 Corinthians.

38. See Matthew 10:29,30 and Luke 12:6,7.